H-S Precision PST-025 mates nicely with a Nightforce NXS 5.5-22 X 56

Since the telescopic sight took off in popularity after WWII nearly every bolt-action rifle in the world and indeed many other types of rifles, wear some sort of magnifying optic as a means to place their projectiles more accurately. The reasoning behind this is simple; if you can't see it you can't shoot it. The magnifying glass makes your target appear bigger, has some sort of crosshair or other reticle to pinpoint the exact spot on the target the shooter desired the bullet to strike. By magnifying the target with a precise aiming point, scopes revolutionized shooting at least as much as rifled barrels (makes bullets fly straighter) and pointed projectiles (helps bullets retain velocity). However as with most things in our lives, things tend to be a bit more complicated than they seem at first glance.

My initial intention of this prose was to help you select the right scope and mounts for your new aftermarket stock, we get many questions about this. True to my reputation, "If you ask him what time it is he'll tell you how a clock is made," you may notice, so goes this story. In other words I will intermix my own opinions of various types of scopes on particular classes of rifles. Its easy to justify this by simply pointing out that there is a place for big, heavy optics, a place for lightweight mid-range optics and a place for low-powered and fixed-power scopes... simply because a certain brand makes great optics most definitely does not mean that what they offer is the ideal for any particular rifle. If I accomplish nothing more than to point your reasoning along certain lines you are more likely to be delighted with your new build. Here are a few rules of thumb:

- Bigger is not always better;

- Match the power range to conditions;

- Consider the weight of the scope;

- Consider the eye relief throughout the power range;

- Choose the right ring and mount height when mounting.

- Mount the scope the correct distance from your eye.

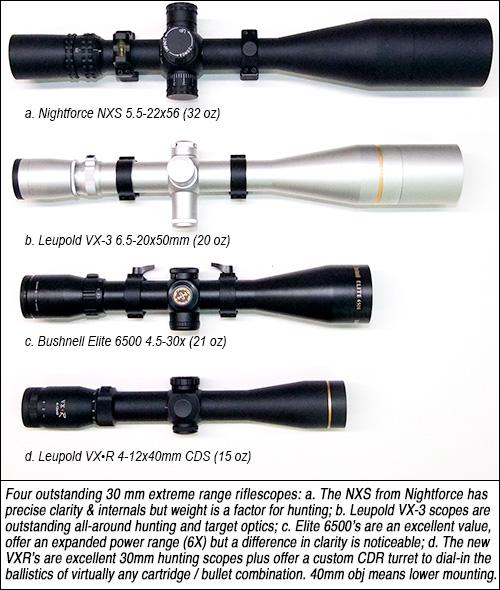

One of the most common mistakes I see on the range is big-honking scopes on typical deer and elk rifles. These folks pay for their mistakes by not only carrying around unneeded weight, but reduced light-transmission (brightness), reduced eye relief and horrible cheek-welds due to the fact that they had to use ultra-high rings to clear that big objective lens from the barrel. Many also suffer from poor-quality optics because they selected a lesser quality glass in order to pay for all that magnification. The sad fact is that unless you pay-up for at least an upper-end Bushnell, Leupold, Nightforce or comparably-priced 20+ power scope the quality of the glass, optical coatings and turret adjustments are going to suffer. Many cheap scopes also suffer from zero-shift through the power range.

One of the most common mistakes I see on the range is big-honking scopes on typical deer and elk rifles. These folks pay for their mistakes by not only carrying around unneeded weight, but reduced light-transmission (brightness), reduced eye relief and horrible cheek-welds due to the fact that they had to use ultra-high rings to clear that big objective lens from the barrel. Many also suffer from poor-quality optics because they selected a lesser quality glass in order to pay for all that magnification. The sad fact is that unless you pay-up for at least an upper-end Bushnell, Leupold, Nightforce or comparably-priced 20+ power scope the quality of the glass, optical coatings and turret adjustments are going to suffer. Many cheap scopes also suffer from zero-shift through the power range.

It is also much harder to hold a high-power scope steady than a low power scope -- you'll see every wobble magnified 20-30X -- wobbles mean more wobbles as you try to correct. You'll also find haze, fog and rain turn your sight picture into large, ill-defined mush. Mirage (heat waves) when amplified make the bullseye impossible to hold upon as it dances in the magnified sun. I'll bet you find your groups shrink when you turn the scope down, not up under these conditions.

I've found the venerable 3X - 9X is about all the scope necessary to make reliable hits out to 300 yards, swore by them for 30 years in fact. I do profess as my eyes age, I've discovered little is given up at short range when moving up to a 4-12X, In fact I've kind of settled upon the Leupold VX-3 in the one-inch 4.5-14 X 40mm objective version, for all-around hunting. My .375 wore this on its first safari, harvesting more than a dozen animals ranging from a 20 yard snap-shot kudu to a 300 yard sable on the Kalahari. When I replaced it on the next African hunt with the new 30mm VX-6 2-12 X 42mm objective model I did so not because I felt I needed to carry a bigger, heavier scope, but because I wanted the 2X setting available if needed for cape buffalo.

I've found the venerable 3X - 9X is about all the scope necessary to make reliable hits out to 300 yards, swore by them for 30 years in fact. I do profess as my eyes age, I've discovered little is given up at short range when moving up to a 4-12X, In fact I've kind of settled upon the Leupold VX-3 in the one-inch 4.5-14 X 40mm objective version, for all-around hunting. My .375 wore this on its first safari, harvesting more than a dozen animals ranging from a 20 yard snap-shot kudu to a 300 yard sable on the Kalahari. When I replaced it on the next African hunt with the new 30mm VX-6 2-12 X 42mm objective model I did so not because I felt I needed to carry a bigger, heavier scope, but because I wanted the 2X setting available if needed for cape buffalo.

Speaking of the .375, eye relief is also an important consideration. Higher magnification optics lose field-of-view for obvious reasons, images are bigger and therefore the width of the image that can be focused is narrower. To increase field-of-view, some manufacturers reduce eye relief, relief and field are always a compromise optically. (Do you want more eye relief or a slightly bigger field of view?) This is also why eye relief varies on a variable power scope. It won't be a big problem on a heavy .223, but belted magnums and up dictate that one get as close to 4" of eye relief as possible, even .243's and .270's can bite if you get your eye too close.

I can just about promise a scope less than less than 3.5" relief from the ocular (on a sporter) will bite you one day when you aren't paying attention. Allow 3.75" at a bare minimum on any magnum, even then you must always pay attention to where you eye is at, and that's tough to do when you're looking at ten-big-points, especially shooting from prone. 4" is ideal on the hunting rifle, and before tightening the rings check the relief at both low (close enough) and high (far enough) powers from the prone position. (When lying down one tends to crowd the scope.)

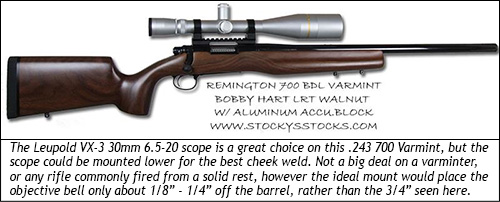

In the above examples the smaller of available objective diameters (both those scopes are available with 50mm+ bells) allows plenty of light at lower settings for dusk and dawn use and allow the use of low mounts. Low mounts allow the shooter to get a better, more solid cheek weld on hunting-type stocks. As any long-range instructor will profess, proper cheek-to-stock contact is imperative not only to gain more control, a steadier hold, but also gives the shooter a solid, repeatable head position for fast target acquisition. This is very important on any rifle.

In the above examples the smaller of available objective diameters (both those scopes are available with 50mm+ bells) allows plenty of light at lower settings for dusk and dawn use and allow the use of low mounts. Low mounts allow the shooter to get a better, more solid cheek weld on hunting-type stocks. As any long-range instructor will profess, proper cheek-to-stock contact is imperative not only to gain more control, a steadier hold, but also gives the shooter a solid, repeatable head position for fast target acquisition. This is very important on any rifle.

This is not to say that big scopes don't have their place. Taking paper targets, prairie dogs or even big game at ranges much past four or five hundred yards reliably under ideal conditions by experienced shooters is simplified by more magnification. Weight isn't much of a consideration either; this is where big scopes and barrels can make good use of big, sometimes even adjustable stocks. Before we get into stocks and barrels, let's touch upon why some scopes weigh more than others.

The single most important element in any magnifying optic is the quality of its glass (prisms or mirrors in some cases.) Light comes in through one end, is refracted (bent) and some portion of the image is magnified and focused upon the viewer's retina (or sensor in the case of a digitized camera). Remember the fuss after they put the Hubble Space Telescope into orbit? Someone had polished the mirror a few microns out-of-spec and the images were blurry. NASA had to spend millions of dollars sending more people up there to correct it. So it goes with the glass in your scope, too.

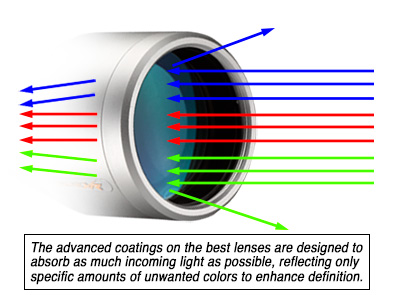

The lion's share of the purchase price of any good scope is in the glass and in the specialized coating(s) they put on the glass. This takes much research and development. A great deal of the light entering any piece of raw glass is diffused and reflected back toward the target, the surface of ordinary glass acts like a mirror. That's not good, we want as much of that light to enter the scope tube as possible so that the image coming out the other end is bright and clear. Much of the light that is reflected away is in specific color-bands. That's why you see a green cast to an old Coke bottle -- the imperfect, raw glass bottle is reflecting more of the green waves back to your eye, which also means the colors objects appear when peering through the bottle seem a different color than they are in real life -- they've lost some of their greens by reflection.

The lion's share of the purchase price of any good scope is in the glass and in the specialized coating(s) they put on the glass. This takes much research and development. A great deal of the light entering any piece of raw glass is diffused and reflected back toward the target, the surface of ordinary glass acts like a mirror. That's not good, we want as much of that light to enter the scope tube as possible so that the image coming out the other end is bright and clear. Much of the light that is reflected away is in specific color-bands. That's why you see a green cast to an old Coke bottle -- the imperfect, raw glass bottle is reflecting more of the green waves back to your eye, which also means the colors objects appear when peering through the bottle seem a different color than they are in real life -- they've lost some of their greens by reflection.

The coatings that are put on the glass of more expensive scopes are precisely formulated by researchers to these goals, color accuracy and "light transmission". Some coatings are even applied to enhance certain color bands and flatten others, engineered to make the color of a deer stand out against the green forest. This is why some lenses look like red, blue or green mirrors, those are the wavelengths they reflect back out of the scope. Works like those "blu-blocker" sunglasses, simply stated, except the coatings on the best scopes are engineered specifically for their intended use. Obviously, this costs money, sometimes a lot of money, but it's not all you are paying for.

The quality and type of glass is also prominent in the cost. In the medical and scientific markets, leaded glass dominates. Leaded glass is a time-tested way to get outstanding imaging, many would argue the best. It is used in the older European (Leica, Zeiss, Swarovski) scope sights as well as many modern brands like Nightforce. Why doesn't everyone use it? Two reasons -- cost and weight. It's about double the price and double the weight. Weight doesn't matter too much for stationary use, such as microscopes or target scopes, but that added 12-16 ounces that is required to mount one on a hunting rifle can and does make a difference to the astute gun-builder. This is why those old Zeiss and the new Nightforce weighs about twice that of a comparable Leupold, Vortex or Nikon... leaded glass. These companies as well as the 21st century European optical operations have improved modern glass through technological advancements in both glass and coatings, so you don't have to tote a two-pound scope to have the finest sight picture available.

Bench and prone rifles are another matter altogether. Here we are free to use the biggest, baddest and heaviest the market has to offer. Unless we are competing in some weight-conscious event, bull barrels, big heavy stocks and scopes are an advantage. In fact, in concert they may be the ideal set-up as the heavier the rig the less it tends to move from things like your blood pulsing through the body. Put your scope at 42 and things you never noticed in your 3X9 become an issue. Still, the builder must still consider how they play together for optimum performance.

Bench and prone rifles are another matter altogether. Here we are free to use the biggest, baddest and heaviest the market has to offer. Unless we are competing in some weight-conscious event, bull barrels, big heavy stocks and scopes are an advantage. In fact, in concert they may be the ideal set-up as the heavier the rig the less it tends to move from things like your blood pulsing through the body. Put your scope at 42 and things you never noticed in your 3X9 become an issue. Still, the builder must still consider how they play together for optimum performance.

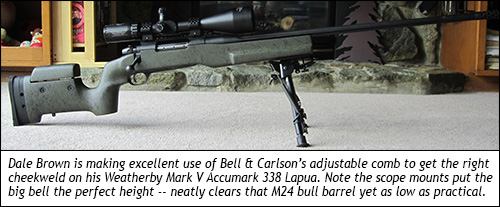

Once one has the receiver (action), generally the next choice is the barrel weight. Heavier barrels are the norm, this generally dictates the use of bigger stocks with forends wide enough to support barrels and settle into rests well. The most recent and popular of these stocks also have a very high, often adjustable cheekrest designed for one simple reason -- proper cheek-weld with big scopes. A big objective bell plus those 30mm+ main tubes must be mounted rather high to clear that big barrel. Even a standard 3X9X40mm scope would require medium rings on this beast, but the scope they generally sport is something that can be dialed-up to at least 20X, with 30X to 40X being at the top of the heap. For this kind of optic, even the current crop of "zero-drop" stocks like the Manners' T4 or the Bell & Carlson 2092 may not be tall enough. This is where the adjustable cheekrest comes into its own.

In order to get your face high enough to use these monsters, it has to be really high. So high in fact, you couldn't remove the cartridge bolt from the rifle for cleaning unless it can be lowered and / or removed. This is why the adjustable cheekrest was born, it's simply coincidence that it also looks great on a big rifle.

Now for the latest crop being harvested by the most dedicated hunters, the truly long-range sporter. These are hunting rifles extraordinaire. Barrel weights range from feather to medium-varmint for the most part, I for one wouldn't want to carry anything much heavier in the field, even to the point of having sporter barrels fluted. You may be aware (or not) that there is virtually no difference in the field accuracy inherent in a perfectly concentric, correctly rifled featherweight barrel and a full-bull bench-gun. At least not for the first few shots. I know a lot of you now think I might be full of it, but think about it -- a perfect bore is a perfect bore. Sure, it might heat up faster where imperfections in the steel cause it to warp when hot, but we are speaking about perfection here, or as close as humanly possible. The lightest barrels may require a bit more loading refinement to "tune" their vibrations, but with the best loads many, many sporter weight barrels are breaking the 1/4 minute mark, 1/2 minute has become routine with the best 5r cut-rifled barrels concentrically mounted in trued receivers with premium triggers, bedded in the best stocks. I'd contend that a good deal of that even is the shooter and/or external conditions, that's plenty good for 500+ yard shooting if the practiced shooter does his or her part calmly and correctly. That's a big "if" but here's how you get started....

You may have made note of the latest introductions from Manners' (Elite Hunters) and H-S Precision (PSS-134) -- vertically-oriented grip stocks with high "zero-drop" combs for sporter barrels. These stocks are designed to take advantage of the best technology the new-millennium has to offer -- high combs for big scopes -- vertical grips for light, crisp triggers -- sporter forends for lighter weight and faster handling. Once you have that tack-driving barreled action, bed it into one of these, mount a lighter-weight big-bell scope (a 30mm VX-6 4-24X52 is perfect) atop and take it to the range and discover for yourself one of the best extreme-range hunting rifles you've ever had the pleasure of owning. Chamber it in something like the .270, 7mm Mag or .280 Improved for deer and plains game; or take full advantage of .300 Ultra's potential for the ultimate long-range sporter.

You may have made note of the latest introductions from Manners' (Elite Hunters) and H-S Precision (PSS-134) -- vertically-oriented grip stocks with high "zero-drop" combs for sporter barrels. These stocks are designed to take advantage of the best technology the new-millennium has to offer -- high combs for big scopes -- vertical grips for light, crisp triggers -- sporter forends for lighter weight and faster handling. Once you have that tack-driving barreled action, bed it into one of these, mount a lighter-weight big-bell scope (a 30mm VX-6 4-24X52 is perfect) atop and take it to the range and discover for yourself one of the best extreme-range hunting rifles you've ever had the pleasure of owning. Chamber it in something like the .270, 7mm Mag or .280 Improved for deer and plains game; or take full advantage of .300 Ultra's potential for the ultimate long-range sporter.